These two MP3s are the only suriving recordings of Mario Maccaferri:

MP3: Bach

MP3: Granados

The plastic guitar

Like the plastic clothespin before it, however, the plastic

ukulele was merely a stepping stone to Maccaferri’s higher ambition of

making a plastic guitar. Let’s face it, ukes hardly represent a great

sonic challenge, but making a guitar out of Dow Styron? That’s

something else altogether!

The Maccaferri plastic guitar debuted in the Spring of 1953. The

introduction was extensively covered by The Music Trades in May of ’53,

which reported a press luncheon thrown by Dow Chemical for Mario

Maccaferri at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York on April 29, 1953.

Described in glowing terms – lunch must have been great – Maccaferri

introduced two guitars and emphasized the resources and cost of

developing his new guitars. Indeed, Amos Ruddock of Dow’s plastic

merchandising department indicated that the project took two years of

testing various formulations of Styron and another Dow plastic called

Ethocel and that tooling up cost around $350,000.

The Music Trades quoted Maccaferri’s speech at length. While referring

to a painting of legendary violinmaker Antonio Stradivarius working at

his bench with a few simple tools, Maccaferri remarked, “A like

painting symbolizing such craftsmanship today would have to suggest the

following elements: 1. Some idea of the enormous industrial resources

and scientific know-how of America today; 2. Not one genius, but a

dozen of them; 3. The pile of money necessary to accomplish the task.”

After citing famous musicians and composers, particularly Paganini, who

played the guitar for their own personal enjoyment and wrote music for

it, Maccaferri continued, “I have always promised myself that one day I

would make a good guitar at a popular price. I had no idea that I would

end up by making a plastic guitar. But when I realized that plastic

would offer me the chance to make a perfect instrument with none of the

shortcomings known in the wooden guitar, it did not take long to decide

and satisfy my life’s ambition. So, I went to work.

“Often in my lifetime of playing guitar, I have had disappointments in

its performance. On many occasions I would find the instrument’s neck

warped or the fretting defective, or the body of the instrument

expanded or contracted, caused by humidity or dryness; thus making my

guitar simply unplayable. Anyone playing the guitar knows what I mean.

“Although today’s fine wooden guitars are the result of 300 years of

guitar making experience, I do not hesitate to say that our 1953

all-plastic guitar compares favorably with any wooden guitar made.

“This all-plastic guitar wasn’t an easy job, as you will understand. We

had a lot of engineering problems and it represents quite a costly

venture for us, but the Dow Chemical Company came up with suitable

materials and we overcame the other problems. To this instrument we

have applied all the improvements that guitar players have been seeking

in it for many years. It has beauty and it is easier to play – it

produces music in perfect pitch, and it has good tone and plenty of it.

And this all-plastic guitar is not subject to any of the shortcomings

mentioned earlier.”

Heavyweight support

While Arthur Godfrey was a great endorser of Maccaferri’s

Islander Ukulele, it might surprise you to learn that Maccaferri

brought his plastic guitar to the world bearing the endorsements of

none other than classical maestros Andres Segovia, his old friend from

the Twenties, and Rey De La Torre, and pop-jazz great Harry Volpe. De

La Torre and Volpe attended the luncheon and performed on Maccaferri

guitars, making the guitar “speak for itself,” after which Maccaferri

himself was prevailed upon to toss up a “lively Neopolitan melody with

skill and dexterity.”

G30 and G40

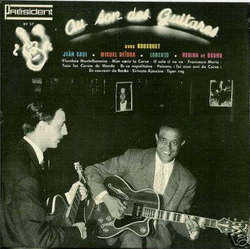

The two guitars Maccaferri introduced at the Waldorf were

described as “full, master size instruments,” “the flat-top, arched

bottom, cutaway model retailing at $29.95; and the DeLuxe Arched Top at

$39.95.” While the denomination is strange, it’s these which would

quickly be known as the G30 and G40, respectively. Both had similar,

Selmer-like shapes with the Maccaferri square cutaway, the former with

a flat top, the latter with an arched top. Pictured in the article are

Maccaferri and Volpe getting down with a pair of plastics, Maccaferri

on a G30, and Volpe holding a striking version of what looks like a G40

with an ivory (a.k.a. “maple”) fingerboard. These are quite remarkable

pieces of technology, each composed of more than 100 separate parts,

not all plastic, to be truthful.

Both had fancy headstocks with Maccaferri’s patented planetary tuning

machines. These were “banjo” style tuners with a 14:1 ratio, a patented

design using three interlocking gears. The G30 had a molded-in bridge

assembly to which the strings attached and a separate plastic saddle

glued in. The G40 had a glued-on archtop-style bridge and a fancy

trapeze tailpiece. Both had two f-holes. Curiously enough, wooden

struts were glued under the tops. The tops were ivory, the sides and

backs done up in a swirled reddish-brown rosewood color. Both were, by

the way, steel-stringed guitars, not nylon stringed instruments like

the Islander ukes. One point to note: early G30s had only the molded

bridge assembly. Some time later a plain metal trapeze tailpiece was

added. This did not serve as the anchor for the strings, but either as

some sort of added support for the bridge assembly or as merely

decoration.

The most curious design elements concerned the neck. The neck was

bolted on the guitar in an early version of a slightly cutaway heel.

The outside of the neck consisted of two pieces of plastic, the outer

back and the fingerboard. The fingerboard bore actual frets and white

position markers (which are actually part of the back and how the parts

are aligned). Inside there’s a metal sheath, referred to as an “armored

neck,” and at the core a piece of wood. This design was guaranteed

never to warp.

Already we’ve described a pretty interesting bit of guitar design, but

wait, there’s more! This neck was essentially a neck-through design.

The inner core ran all the way through the body to the endpin. There it

was notched and had a threaded bolt running perpendicular to it. This

bolt had a couple nuts above and below the neck core and was slotted.

By removing a metal plug from a hole on the top of the guitar down at

the bottom of the lower bout, you can use a screwdriver and basically

adjust neck tilt and therefore action by tightening or loosening this

bolt!

OK, we have a plastic guitar with a warp-proof neck, perfect

intonation, adjustable action and pretty natty faux-rosewood looks.

Let’s cut to the chase. How does it sound? Well, beauty is in the ear

of the beholder, but in my opinion pretty good, indeed. The tone is not

really like a typical wood sound. In some ways it’s sort of like an

acoustic variant of the Strat’s out-of-phase sound, kind of funky. In a

good one, the balance and sustain are quite remarkable. Of those I’ve

personally played, I’ve found the newer ones to have better sound, and

I prefer the tone of the flattop G30 to the more upscale archtop G40.

If I were a recording artist, I’d consider a G30 as an indispensable

part of my studio arsenal, and would never apologize for the tone.

More toys

With all the fuss over the introduction of Maccaferri’s plastic

guitars, they went over among guitarists, well, like a plastic guitar.

Guitar players, as you know, are a pretty conservative lot when it

comes to instruments, and the Maccaferris probably were never able to

shed the “toy” image. Some reports suggest that quite a few of these

guitars were sold, however, how many is unknown.

Despite the luke-warm reception of the plastic guitars, Maccaferri

forged ahead with his plastic instrument empire. In the Winter of 1953

the Islander Baritone Ukulele was added to the line, just in time for

the holiday season.

In a February 1954 ad in The Music Trades, the Maccaferri line included

the new Islander Baritone Ukulele ($12.95), the G30 ($35.95 with case)

and G40 ($45.95 with case) guitars, the U150 Islander Ukette ($1.00),

the C100 Chordmaster attachment, the U400 Islander Ukulele ($3.95), the

U600 Islander DeLuxe Ukulele and MU25 Midget Uke ($.25). Both Islander

Ukes came in a “Combination” package (UC500 for $4.95 and UC700 for

$6.95); just what that combination consisted of is unknown, but was

probably the Chordmaster and accessories, as before.

In an undated catalog supplied by Michael Lee Allen, probably from

around this time based on pricing, the Maccaferri uke line consisted of

the Islander uke ($4.50 alone, $5.70 with Chordmaster, books and

accessories), the T.V. Pal, a stripped down version of the Islander

($1.75), the Islander DeLuxe ($5.95), and the Islander Baritone

($12.95).

The Islander Guitar

Also introduced in February of 1954 was the No. G16

“Popular-Priced” Islander Guitar. This was basically a standard

acoustic flattop version of the fancier G30. This was 35″ long, 13″

wide and 4°” deep. It had a round soundhole and the same bridge

unit as the G30. The neck had the same design as its bigger brothers,

although it is unknown if the action was adjustable as on the f-hole

models.

The coolest thing about the G16 was the choice of finishes. It could be

had with mahogany grain body, ivory top and ebony fingerboard, with

mahogany grain boy and top with an ivory fingerboard, and with an ebony

grained body and top with ivory fingerboard. These had the typical

Maccaferri headstock with planetary tuners.

The classic Maccaferri G30, G40 and G16 plastic guitars were kept in

the line until the instrument business was ended in 1969, although

production was sporadic during these years. The Maccaferris’ typical

approach was to make a large batch of products and then inventory them

until more were needed. How many of these guitars were actually

produced over the years is impossible to tell, but there were quite a

few sold, although certainly not approaching the 9 million uke mark.

When the remaining assembled stock was liquidated in the early ’90s,

nearly 5,000 instruments were still available.

The Romancer

In June of 1957 Maccaferri introduced the Romancer Classic Style

Guitar, No. R20. This was advertised as a “standard-size” guitar, 35″

long, 13″ wide and 4°” deep. It featured Maccaferri’s patented

planetary tuners and fancy headstock. The body and neck had now become

a single molded unit, more like the ukuleles than the elaborate bolt-on

affair on the G30/G40/G16s. The copy alludes to “Wood-armoured neck and

body,” which we can presume to mean there was wood reinforcement inside

the neck and probably wooden struts. The neck and body were made of

“grained ebony” plastic, while the top and fingerboard were ivory,

silkscreened with decorations. The body had music staves looking like

ribbons and five different musical scenes of teens getting down. One

was a trio (a la Kingston), two guys solo, a little jazz combo with a

piano (a la Nat King Cole?), and a guy and gal duo. The position

markers on the fingerboard were little pictures. The Romancer came with

a rope strap, guitar method and pick, “very easy to play, and

luxuriously finished – the ideal guitar for any type of music – from

classical to popular, folksong, Calypso, Rock ‘n Roll, etc.”

ShowTime

Among the later plastics was the ShowTime classical guitar shown

here, a nylon-stringed axe with teen scenes which, based on the look of

the teens is probably circa 1960 vintage. This looks to be another

iteration of the Romancer. Although the headstock contains Maccaferri’s

trademark planetary tuners, this guitar has a molded neck attached to

the body similar to the Romancer. Instead of inlaid metal frets, this

has plastic frets molded into the fingerboard and painted silver.

Despite this unflattering description, again the tonal response is

quite good. Hey, it isn’t a Ramirez, but for what it is, a plastic

classical, it has a distinctive character.

Electrics

Among the many whimsical plastic Maccaferri designs of this era

was a brief early ’60s excursion into electric guitars with the small

Maestro electric tenor guitar. This guitar had four strings and a short

18*” scale, and contained its own battery powered amplifier. Strings

attached either to a trapeze tailpiece or onto the bridge, as the

player desired. The Maestro had one single-coil pickup at the lead

position. Tuners were the basic open-backed variety.

Sometime during this period Maccaferri also added various plastic horns

to his repertoire.

Introducing the Beatles…

The last notice of Maccaferri’s instruments occurred in the

July, 1964, The Music Trades, in which the new “Beatles” line was

discussed. The company was now identified as Mastro Industries, Inc.

Introduced in March of ’64, significantly at the Toy Show in New York,

the Beatles line marked a final burst of success for the Maccaferri

venture. Maccaferri had obtained the exclusive U.S. license to market

official instruments using The Beatles name.

Included were four Beatle guitar models made of “Beatle Red” and

“Beatle Orange” injection molded polystyrene plastic bodies. The ivory

tops included brown printed portraits of the Fab Four with

reproductions of their signatures. Two four-string tenor guitars were

offered, the Jr. Guitar and the Four Pop, and two small-bodied

six-strings, the Yeah Yeah and the Beatle-ist. Construction appears to

be similar to that of the ShowTime. Each came with instructions, song

book and a pick.

The Mastro Beatle line also included a set of Ringo Drums, plastic

bongo drums and a plastic banjo. There was also a miniature Pin-Up

guitar which was a 5″ replica of the real Beatle plastic guitar!

According to the article in The Music Trades, Mastro had already

shipped 500,000 of the Beatle guitars and was projecting two million by

the end of the year. Whether or not Maccaferri ever met that projection

is unknown, but Beatlemania, too, began to spread out and change

quickly as the fans grew older and the pace of the decade picked up.

1965 plastics

A good picture of the mature Maccaferri Mastro line can be seen

in the 1965 catalog. Top of the line were the G-40 archtop and G-30

flat top, followed by the Showtime No. 1020 (sans decoration) and

Romancer No. 1010. By this time both the Showtime and the Romancer had

an amazing neck design which featured a tension screw inside the body

at the heel accessible with a long screw driver. Tightening or

loosening the screw changed the neck tilt and therefore the action.

Also available were the G-16 Islander Guitar, the 35″ Mastro G-10

Guitar with armoured neck, and the 31″ Mastro G-5 Guitar.

In addition, there were two versions of the 30″ nylon-stringed Sonora

Guitars No. 727. The A-SH was in a marbled woodgrain color, while the

IC was in cream and black. Under these were the No. 500 TV Pal Guitar

in two colors (PIC) or woodgrain (A-SH). The No. 775 Western Guitar

featured singing cowboys, bucking broncos, boots and saddles on the

front.

Still in the line were a small Maestro electric six-string and tenor

guitars. The GTA-5 Electric Guitar was a 32″ woodgrain-colored

non-cutaway acoustic with a small humbucker attached near the bridge.

The wiring came out the treble side through a tube into a small housing

with a volume control and jack for a mini-plug. The CT GTA-5 Tenor

Cutaway Electric Guitar was basically a four-string version, with the

optional string attachment at the tailpiece or bridge. These guitars

had a new patent-pending design which featured a rigid metal beam which

ran through the guitar from the nut to the heel, detouring toward the

back once inside the body. Both were played through the matching TA-5

Mastro Amplifier, a small 5-watt portable transistor amp with a 6″

speaker, operating off two 9-volt batteries.

The recently introduced Beatle line was also available, of course.

Beatles guitars included the 30°” Beatle-Ist Guitar (No. 340), the

22″ Beatles Yeah-Yeah Guitar (No. 330), the 21″ Beatles Four Pop Guitar

(No. 320, four-string), and the 14°” Beatles Jr. Guitar (No. 300).

The 22″ Beatles Banjo (No. 350) was offered, as were the Beatles Ringo

Snare Drum (No. 380), the Beatles Beat Bongo (No. 360), the Beatles Big

Beat Bongo (No. 370), and the Mastro Beatles “Pin-Up” Guitar, miniature

guitars you could clip on your shirt. All had portraits and signatures

of the Fab Four on the front.

Two cutaway baritone ukes, the Mastro TV Pal (No. 610) and the Islander

(No. 410), were offered, as well as the woodgrained Mastro Cutaway

Tenor Guitar (No. CTG-6) and the TV Pal Cutaway Tenor Guitar (No. 666).

Ukes included the Mastro Uke (No. 750), the Islander Uke (No. C-400),

the Mastro Jr. Guitar (No. 725, a uke with six-strings) and the TV Pal

Uke (No. 120). Two Chordmaster units were available, the Automatic and

the Visual Chordmaster, complete with little lights to let you play the

uke without lessons! The Mastro Ukette (No. 100) was still around, as

well as the Mastro Banjolele (No. 110) and the Banjo Uke (No. 520).

Two plastic violins were offered, the cream-colored Square Dance Fiddle

(No. 700) and the woodgrained Stradivarious Violin (No. 1000), both

with plastic bows.

Finally, six wind instruments were available, a trumpet in gold or

cream, a saxophone in gold or red, and a clarinet in gold or black.

There were also six percussion instruments, a set of bongos, three

maracas (rumba, bolero and rhythm), castanets and a remarkable plastic

snare drum.

Gitarina

In 1966 the Mastro plastic line continued unabated with several

new curious additions. Most curious was the Gitarina (No. 222), 25″

double-cutaway hollowbody acoustic basically looking like a Strat with

an asymmetrical three-and-three headstock. This had 20 frets, the end

of the fingerboard cut in a groovy stairstep design. Soundholes were

twin “split-ribbon” shapes.

Also new were two electrics, the GTA-10 Electric Guitar and the Teen

Electric Guitar. The GTA-10 was basically a 35″ woodgrained Romancer

(with neck-tilt adjustment) and the Mastro pickup. The Teen was a

woodgrained 30″ guitar with a small transducer pickup. Both could be

played through the TA-5 amp, or the new TA-10 10-watt amp, or the

smaller TA-3 3-watt amp (powered by 1° volt batteries). If you

wanted to plug these amps in, a new AC Power Transformer was now

available.

Summer of Love

In 1967 Mastro enhanced the line once again. Most of the old

plastics were still available, but new things were added. The Gitarina

was the main focus of expansion. On the downside was the Monkey (No.

102), a tiny uke version of the acoustic Strat, now with a four-in-line

headstock. Upside was the Disco Cutaway Guitar (No. 352), basically the

Gitarina with a small pickguard sort of surround on the lower

soundhole, triple rectangle fingerboard inlays, and a fancier bridge

with tailpiece.

New, too, was the 30″, nylon-stringed Riviera Guitar (No. 303), a

slightly offset double-cutaway with ribbon soundholes with little

circles in the middle, a six-in-line headstock and optional bridge or

molded tail string attachment. An upscale version of this was available

called the Jet Star, with more coloration, a pickguard surround on the

lower soundhole, a metal tail, and with triangular inlays. The Riviera

(No. 551) was an electric version with a transducer pickup attached to

the lower bout connected to the Mastro 4.11 amplifier.

The Sonora acoustic got a lift with the addition of the nylon-stringed

Deluxe Sonora (No. 325). This had trapezoidal inlays, a black pickguard

and a metal tailpiece. The nylon Mastro G3 Guitar (No. 358) was

basically the same guitar with traditional worm-gear tuners, rather

than friction pegs. The woodgrained Mastro G5 Guitar (No. 452) was

virtually the same, too, except for hollow rectangle position markers

and the through-body metal beam reinforcement.

Also new was the 32″ cream-and-colored Mastro Classic Guitar (No. 451),

pretty much identical to the G3. This was available as the Classic

Electric Guitar (No. 552) had the same transducer and 4.11 amp as the

Riviera electric.

Plastic denouement

All this new development ended up as the end of the road.

In around 1967, Mario Maccaferri had an episode with his heart which

precipitated some new thinking about his priorities. Other events were

conspiring to confirm his conclusions.

Not long after his recovery, in 1969, Maccaferri plastic guitars

received a bad review. This was, after all, the era of The Graduate,

the movie which almost single-handedly defined “plastic” as

counter-counter-culture. Mario, never one to brook irrational

opposition, decided if people were going to criticize his work, he

would stop giving them something to criticize. Despite the fact that a

huge number of plastic guitars were in various stages of completion,

Mario said, “No more,” and all parts were boxed up and put into storage.

At the same time, in 1969, Maccaferri decided to get out of the plastic

instrument business altogether. The designs, molds and other equipment

for making his more toy-oriented plastic creations were sold to

Carnival industries, another plastic novelty company. Carnival never

figured out what to do with the Maccaferri legacy which it purchased,

and no Maccaferri plastic instruments were ever made again.

8-Track tapes

Never ones to remain idle, the Maccaferris continued to work in

plastic, however. In around 1970 or ’71, RCA came to Mario with the

idea for an 8-track cassette, needing plastic housings. Mario designed

and produced the first 8-track cassette housing. Unfortunately, RCA had

his design and process copied, closing out a major business

opportunity. Nevertheless, Maccaferri turned his invention to good

turn, and he sold many of these 8-track housings to other

manufacturers. Eventually, in the later ’70s, Maccaferri expanded into

making cassette tape housings, as well.

Saving the reeds

In around 1981 several events occurred to wind down Mario

Maccaferri’s commercial ventures. One event was simply that Maccaferri

was getting tired of making cassette housings, and wanted to get out of

the plastic business. Another was that the city of New York wanted

Maccaferri’s building and purchased it from him. Rather than beginning

over again at a new location – Mario was already 80 – Maccaferri

decided it was time to stop and to liquidate the factory.

In 1981 almost all of the equipment was auctioned off for a relative

pittance and Mario retired. However, Maria was not ready to stop, and

diverted the auctioneer from the reed-making equipment. She asked Mario

to give her the reed making business. She had, after all, been involved

with it since she was 16 years old. Mario agreed and signed the reed

business over to Maria Maccaferri.

From that day on until his death, Mario would always tell Maria that

“you’re the boss” when it came to the reed business, although Maria

adds that Mario was really always the boss.

As of this writing Maria Maccaferri continues as President of the

French American Reeds Manufacturing Company, making reeds primarily for

various private label retailers, rather than put the effort into

advertising and marketing the Maccaferri brand. Among those labels

which are really Maccaferri reeds, by the way, is the name Selmer…

Plastic violins

Although commercial production of instruments had ended at the end of

the ’60s, in his later years Maccaferri continued his interest in

making instruments. For the remainder of his life he went to his

workshop every day at 7:30 a.m. and continued working on various

projects, including the development of a remarkable travel guitar, a

classical guitar which folded up into its own body – without detuning –

becoming the size of a shoebox, and a radical new plastic violin

design. This violin project was completed in 1990 and a public debut

was conducted at the Weill Recital Hall at Carnegie Hall. The critics

were less than generous about the violin, but Mr. Maccaferri was feted

by a number of chemical companies for his pioneering work in the field

of plastics.

Although I never had the pleasure of his acquaintance, there has never

been an account of meetings with the Mastro Maestro which didn’t relate

his warm nature and genuine enthusiasm and camaraderie with anyone who

loved guitars.

Mario Maccaferri passed away on April 16, 1993, at the age of 92.

Many Maccaferri plastic guitars and other instruments remained unsold

after 1969 and were stored at the Mastro warehouse in the Bronx for

many years. Periodically lots of these would be liquidated to hopeful

dealers, the first beginning in 1982, with a final purge being made

shortly before Maccaferri’s death in 1993, with many instruments going

both to A.S.I.A. and Elderly Instruments in Lansing, although most of

these have been sold by now. There should be little trouble in finding

new old stock Maccaferri plastics, and they are well worth seeking out,

particularly the G30 and G40 models, with their funky tone and

fascinating technology. Much harder would be finding Mario Maccaferri’s

older Selmer and Maccaferri guitars, which now command prices well into

the five figure range.

21st Century guitars?

In retrospect, there’s no denying that Mario Maccaferri’s vision

of inexpensive but good guitars made out of plastic was Quixotic, but

the time has come to recognize them for the visionary instruments they

were. It’s highly unlikely that the idea of building acoustic guitars

out of injection-molded plastic will prove to be the wave of the

future, but increasingly luthiers are searching for alternative

materials to the scarce tonewoods traditionally put into guitars. And,

at this writing, at least one company, Kuau Technology, Ltd., of Maui,

Hawaii, markets RainSong guitars, steel-string and classicals made

entirely out of graphite, advertised as “stable and durable, impervious

to climate,” objectives laid out by Mario Maccaferri way back in 1953.

So, who knows? Who would have thought how prophetic were the words of

Mr. Robinson when he put his arm around Dustin Hoffman and said,

“Plastics?”

However the next century turns out, we can certainly conclude that

Mario Maccaferri contributed mightily to the guitar cause over the

course of the 20th Century, as a trailblazing classical guitarist,

award-winning luthier, and plastics innovator, the father of the

plastic guitar. That Mario Maccaferri’s best-known achievement should

be his plentiful, accessible and totally delightful plastic instruments

may not be totally adequate, but then again, how many of us are so

fortunate to leave living epitaphs that serve as memorials to our

creative vision?